Women Artists at Henie Onstad Kunstsenter — A Selected Catalogue of Works Exhibited from 1970 to 1988

Women Artists at Henie Onstad Kunstsenter — A Selected Catalogue of Works Exhibited from 1970 to 1988

Flashback

I spent February 2017 at Henie Onstad Kunstsenter, digging through the archives, exploring the exhibition spaces, and venturing out a bit into the surroundings of Høvikodden, mostly contemplating the frozen fjord.1 The tranquility of this place doesn’t seem to vary all that much, but in wintertime it is particularly still. Against a background of snow, both the Center’s architecture and its outdoor sculptures appeared sometimes poignant, other times ghostly, with layers of aesthetic references from different decades.

It presented itself as a good retreat; however, I couldn’t immerse myself entirely into it, as at that time massive anti-government protests were occurring in Bucharest, the place I come from. During the day, I was engulfed by the quietness of this remote and peaceful place, while at night I would watch the troubling news from back home and elsewhere in the world. Caught between these two worlds, I began browsing the Henie Onstad archive in search of material I could engage with and whose reactivation could make sense in a broader context, for myself and for others. I found myself paying particular attention to the institutional framing, the conditions and context, rather than the actual events, exhibitions, and displays documented in the archive. I was preoccupied with who assembled the collection and through what means, rather than what the collection contained. How the architects who designed Henie Onstad were selected, and how the costs for the building were covered, instead of what style it was built in. Who the institution’s public has been, and whose taste and decisions the exhibitions have reflected, rather than which schools and trends the artists belong to. These were the questions the folders in the archive and the publications in the library raised for me, through which I was trying to make the institution’s memory meaningful to myself and to the present day.

It was only toward the end of my stay that it struck me how few women artists the museum exhibited in its first decades, with even fewer represented in the collection.

I knew this state of facts had to be seen in a much broader frame, one that took into account how women artists fight for representation still today.

I knew this state of facts had to be seen in a much broader frame, one that took into account how women artists fight for representation still today. I even wondered if it was worth highlighting this situation, considering the otherwise innovative character of Henie Onstad and the many experiments it has engaged in since its founding in 1968, especially in the performative arts. In her PhD dissertation on Henie Onstad’s exhibitions, curator Natalie Tominga Hope O’Donnell also points out that “one area in which the Kunstsenter did not show openness was in terms of gender representation. There were only a few solo exhibitions by women artists in the early years of the Kunstsenter, and they were only occasionally represented in group shows, particularly in surveys of textile art.”2 O’Donnell further notes that this difference in gender representation was not seen as an issue at that time, and we are “retrospectively attributing such representative considerations, which is not to say that they are not valid.” I knew it was not up to me to suggest a recuperation of marginalized positions in the early history of the Center’s exhibitions and collection—this rather being the task of its dedicated curators. I also wondered if a consideration of gender representation wasn’t too external a criterion for approaching the rich offline archive of the institution, and also if perhaps it wasn’t so urgent an issue either, given how the times have changed and how the recent and current teams at Henie Onstad have been much more attentive to the political frameworks of each exhibition. Then the fall of 2017 brought the tsunami of the #MeToo movement, and suddenly what seemed only an intuition—that advances in civil rights should not be taken for granted, that emancipation is reversible, that there are still more voices kept silent than those able to speak out, that history needs to be constantly revisited and reclaimed from peripheral positions—appeared with full clarity, thus giving more legitimacy to my initial impulse.

For several very short days (as they usually are in February), I had been on a frantic “good witch hunt” to help affirm my position, checking every name that wasn’t familiar to me, looking at footnotes to dig out all the details, searching through exhibitions that bluntly describe themselves as presenting various “national” art scenes while underrepresenting women (even an exhibition of Soviet prints from 1975), and navigating between exhibitions organized by medium (photography and painting dominate, punctuated by sculpture, installation, and textiles and other such “craft” objects, with some notable standouts, such as the computer art exhibition from 1971).3 I began to understand how, in many cases, the exhibitions were built around circumstance or followed diplomatic positionings. The exceptions to this rule also began to jump out, such as the six solo exhibitions of the Czech-born Norwegian artist Zdenka Rusova from 1971 to 1989, the last two presenting works that she donated to the collection. I happily found multiple women in an exhibition of Sámi art from 1981, and wondered, with some frustration, why Istvan Korda Kovacs’s photographs of Barbara Hepworth’s sculptures, exhibited in 1971, were more interesting to show than Hepworth’s actual works (although perhaps the photographs were just more accessible).4

I happily found multiple women in an exhibition of Sámi art from 1981, and wondered, with some frustration, why Istvan Korda Kovacs’s photographs of Barbara Hepworth’s sculptures, exhibited in 1971, were more interesting than Hepworth’s actual works

In 2018, Nosotras Proponemos, a group of women art workers from Argentina, proposed a series of events across their home country to take place on March 8—International Women’s Day—as part of their call for gender parity in museums and art institutions. One of the participating museums, the National Museum of Fine Arts in Buenos Aires, chose to emphasize works by women artists in its collection by literally putting them under a bright light while keeping the rest of the museum in semidarkness.5 A simple intervention in the museum’s display methods proved to be a powerful metaphor for the absence of women in the narrative of art history—or at least as it is told by institutional collections. Opening and closing the well-organized folders in the drawers of the Henie Onstad archive became for me a similar gesture, where I could pick up one folder and shake the dust out of it, even if the materials inside were scarce or at a first glance not particularly revealing.

The gesture I’m attempting to enact through this essay is of a similar nature to the gesture of the Argentinian museum: highlighting the less visible, making a dramatic extraction, and breaking away from the traditional categorizations of art history (be they chronological, thematic, or stylistic), to offer an alternative image of the Henie Onstad collection, collaged from the extracts of a marginalized history—one that existed but was more accidental, and which is now mostly hidden in the drawers of the archive. I chose to approach it as a nonnarrative archive, disrupting its historical character, for its official structure and systemizations appeared to be too strongly identified with the linear, dominant art history that centers on white male artists.

Make the Past Serve the Present6

Henie Onstad was established specifically as an interdisciplinary art center and it aimed, according to its first director, the Norwegian pianist and art historian Ole Henrik Moe, to reflect the art of its time and even to make a place for “the art of tomorrow today.” However, the Center is nevertheless based, following inscribed institutional tradition, on a collection, which functions in different temporalities and solicits a set of conditions—from the way it is stored and indexed, to its displays, permanent or temporary, and its contextualizations.

The Center is nevertheless based, following inscribed institutional tradition, on a collection, which functions in different temporalities and solicits a set of conditions—from the way it is stored and indexed, to its displays and contextualizations.

In the book (Re)Staging the Art Museum, Henie Onstad’s current director, Tone Hansen, speaks about institutional memory, the impossibility of keeping the art institution removed from changes in society at large, and the need to look at one’s historical ground and political pressures from the outside, which can often, and increasingly so in recent years, threaten the public good. In terms of a museum, such pressures can turn an institution into a fetish object of private and state corporate investment, causing it to operate in the same patterns as any other self-celebratory asset. Hansen is aware that, when it comes to Henie Onstad itself, “history works in the institution and may be resurrected actively, or reactively.”7In her practice both as a curator and as a director, she has often taken the institutional framework as a starting point for discussion. In this sense, it’s worth mentioning one particular exhibition, In Search of Matisse (2015), and its accompanying publication, Looters, Smugglers, and Collectors: Provenance Research and the Market,8 which came out of a process of looking at the provenance of the core collection, which was donated by Sonja Henie and Niels Onstad, the Center’s founders and namesakes.9 Even if, as Ana María Bresciani, curator at Henie Onstad and a researcher deeply involved in the project, states, the impetus for the provenance investigation was a legal claim from a private family in relation to a Henri Matisse painting that had been confiscated during the Second World War,10 the institutional self-examination it caused was significant. Externally, the main result of the project was the restitution of the work to the family, and, internally, the awareness this case raised about the unclear histories of the works in the Henie Onstad collection, and the subsequent efforts to trace them back, led to a resituating of the collection on more ethical pillars.

Through this practice of looking at one’s own institutional foundations and engaging with present-day topics from the perspective of one’s locality and history, Henie Onstad has managed in recent years to challenge the idea of what the “present” actually means, in relation to how “the art of tomorrow today” was conceived by Moe in the institution’s early years.11 By understanding tradition as being “founded on things that have had within themselves the inner strength to survive,” Moe perceived the “contemporary” as requiring “the ability to select from our own time those things which have in them the innate inspiration and tenacity necessary for survival.”12 Moe was open to an art that did not commit to the long-duration rules of the past, that obliterated the borders between different mediums and between artwork and spectator, that was international, and, moreover, that was able to transgress the triviality of the everyday. He sought an art that would “mak[e] us feel happier people in these grim and anxious times,”13 thus showing an affinity for and an understanding of the currents and experiments of the epoch, of the multidisciplinary, and of pop culture. Still, he was immersed in a Western position that privileges the decontextualized art object or event—be it enlightening, educational, or just enjoyable—which is, still today, the dominant paradigm of many art museums. This perspective not only assumes the existence of a universal, autonomous language of art (which can be appreciated by people in both Norway and Japan, to refer to Moe again), but also takes for granted the intrinsic value of this art, which is perceived as capable of offering connectedness to one’s own time and also maintaining relevance over time.

It is this very idea that is increasingly challenged today, not only on representational grounds but also for its assumptions, with curators, artists, and scholars alike contesting the mechanisms that usually make possible the production, selling, and presentation of art, and calling for their reconfiguration. Before aesthetic revisions can be made, however, questions need to be asked. Questions such as, to raise just a few: Who determines the canons of art and how are they maintained and reproduced? To what extent does entering these canons depend on access to artistic education and to exhibition opportunities? How are they reinforced through economic domination?

Who determines the canons of art and how are they maintained and reproduced?

What has happened more recently at Henie Onstad is a process of countering the paradigm of the present as understood by Moe and situating the institution in a “dialectical, multitemporal contemporaneity,” as an “action that seeks to reboot the future through the unexpected appearance of a relevant past,” to borrow the words of art historian Claire Bishop.14 Rather than trying to seek out expressions of avant-gardes and to imagine oneself already in the future, a contemporary museum such as Henie Onstad (whether it likes calling itself a “museum” or not) needs to constantly reposition itself toward its own past and to negotiate its present, not only by being open to current debates but also by exploring and illuminating its own histories. Our times prove to be again, just like fifty years ago, “grim and anxious,” and often these circumstances are used by political and economic decision-makers to force certain agendas on cultural institutions, usually translating into demands for increased audience sizes, for entertainment rather than critical discourse, for perpetuation of the status quo rather than discussion of it. Unlike fifty years ago, however, we have come to understand that art’s role is not so much to make us happier, as Moe expected, but rather, among other things, to raise questions, to dislocate preconceived and inherited ideas, to turn up the spotlight on certain issues while dimming it on others that have been overly exposed—all of which doesn’t make art less enjoyable or reduce its aesthetic value. The advantage of a museum over other types of art institutions is that it can afford to be open for these discussions without much external help; its collections and archives serve as important assets that carry so much more than mainstream narratives.

The advantage of a museum over other types of art institutions is that it can afford to be open for these discussions without much external help; its collections and archives serve as important assets that carry much more than mainstream narratives

Élan vers l’avenir15

What follows is a short catalogue simulation with works by some of the women artists who exhibited at Henie Onstad in the years between 1970 and 1988. It is a subjective selection of works taken out of the frames of the exhibitions in which they were originally shown and also not put in the context of the artists’ larger practices. This catalogue is meant to give a hint of a parallel history that could have been written at Henie Onstad, had women artists been given a more prominent space of representation. Highlighting this history makes the institution look even more progressive than it actually was. While some of these artists were given due recognition in their original time periods (for example Magdalena Abakanowicz, whose exhibition was vast and whose works were acquired for the collection), other artists were shown from pure intuition or due to the experimental nature of their work, even if they were hardly known at that time, such as Howardena Pindell. The fact that many women artists were shown in medium-specific exhibitions, such as textile art, is a shortcoming of the curatorial approach of the epoch; this was also the general approach to exhibiting men artists (many of whom were working in painting, which was exhibited significantly more often during these decades). Of course, more women than those included in this selection have shown at Henie Onstad (though not so many more). I haven’t included any works by Zdenka Rusova, for she was overly present both in the exhibitions and in the collection—and the excess of her presence is rather the exception that confirms the rule of the scant representation of women artists.16 So, here, her absence achieves the same, highlighting her as the one exception. I also haven’t included the artists who participated in the Center’s live program, as I felt they needed a different approach, and moreover this history has recently been addressed in great detail, in particular by the publication Mot det totale museum.17 It is also only in recent times that museums have started to collect live art in forms other than its documentation. What I present here is most of all a curatorial selection, a walk through the archives, a collection of “seeds for a random garden,”18 for a future in which these women’s work is looked upon with the same attention as that of their male colleagues.

This text is part of the anthology It Must Out—Making Exhibitions Since 1968. The book is compiled of commissioned texts about exhibition histories at Henie Onstad Kunstsenter from 1968 to 2002. Edited by senior curator Ana María Bresciani, It Must Out is an attempt to disclose the institution’s politics of identity through the writings of external curators that were part of a residency at the Center. The themes in the projects’ analysis like technology, dematerialization, identity, and representation, broaden curatorial perspectives within contemporary art exhibition processes.

Contributing writers are Biljana Ciric, Cora Fisher, Robin Lynch, Amanda Parmer, Anca Rujoiu, Nicole Smythe-Johnson, Tommaso Speretta, Elise Storsveen, and Raluca Voinea.

From the shop

Referanser

-

Special thanks to Milena Hoegsberg for inviting me to the Pendaflex residency, to the Henie Onstad staff for tolerating my ghostly presence in and around the institution, and to Ana María Bresciani for her extreme patience, as well as for her valuable editorial feedback and consultation on specialist matters.

-

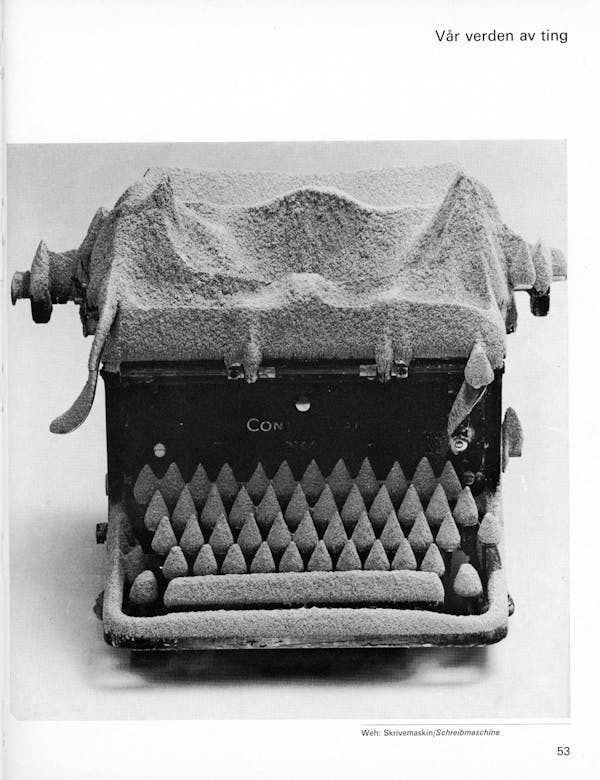

Natalie Tominga Hope O’Donnell, “Space as Curatorial Practice: The Exhibition as a Spatial Construct. Ny kunst i tusen år (1970), Vår Verden av Ting—Objekter (1970), and Norsk Middelalderkunst (1972) at Henie Onstad Kunstsenter” (PhD diss., Oslo School of Architecture and Design, 2016).

-

An exhibition with performances and actions, called The British Thing (September 23–October 15, 1972) is also a standout, but it was much more connected to the live arts program that Henie Onstad was brilliantly staging at the time. For more on the computer exhibition, Electra, see Robin Lynch’s essay in this volume, p. 142.

-

As an example of the current team’s ongoing corrective to Henie Onstad’s historical lack of supporting women artists, Hepworth is indeed now represented in the collection. The Savings Bank Foundation DNB recently purchased a sculpture by Hepworth, Curved Form (Bryher II, 1961), and it is on permanent loan to Henie Onstad.

-

Victoria Stapley-Brown, “Argentina’s Female Art Workers Call for Gender Parity on International Women’s Day,” Art Newspaper, March 8, 2018, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/movement-of-women-in-the-arts-in-argentina-calls-for-gender-parity-in-representation.

-

The slogan “Make the Past Serve the Present” appeared on a banner by the Scratch Orchestra that was presented in The British Thing at Henie Onstad Kunstsenter on October 9, 10, and 13–15, 1972.

-

Tone Hansen, “Learning from Critique,” in (Re)Staging the Art Museum (Høvikodden: Henie Onstad Kunstsenter; Berlin: Revolver, 2011), 93–105.

-

See Tone Hansen and Ana María Bresciani, eds., Looters, Smugglers, and Collectors: Provenance Research and the Market (Høvikodden: Henie Onstad Kunstsenter; Cologne: Walther Koenig, 2015).

-

Nineteen of the twenty paintings in the core collection that are dated before 1945 were bought by Henie and Onstad while in exile in the United States, before they returned to live in Norway in 1960. The twentieth painting is Henri Matisse’s Woman in Blue Dress (1937), which the Nazis looted from its Jewish owner, Paul Rosenberg, in 1940; Henie Onstad restituted it to Rosenberg’s heirs in 2014. The research project at Henie Onstad sought to ascertain the provenance of the nineteen other artworks and trace the relationships between the market and the donors’ collection.

-

Ana Maria Bresciani, “A Collection’s Provenance Questioned,” in Hansen and Bresciani, Looters, Smugglers, and Collectors, 169–261.

-

Moe was director of Henie Onstad between 1966 and 1988.

-

Ole Henrik Moe, “A Museum for the Future,” PRISMA, no. 1 (August 1968): 18.

-

Moe, “A Museum for the Future,” 24.

-

Claire Bishop, Radical Museology; or: What’s “Contemporary” in Museums of Contemporary Art? (London: Koenig Books, 2013), 61.

-

Elan vers l’avenir (Momentum into the Future, 1967) is the title of a work by artist Sonja Ferlov Mancoba, presented in the catalogue selection portion of this essay.

-

Most recently, Henie Onstad held a solo presentation of Zdenka Rusova comprising the works that the artist donated to the Center. The retrospective exhibition Zdenka Rusova—A Norwegian Pioneer was curated by Tone Hansen and took place March 29–July 28, 2019.

-

Lars Mørch Finborud, Mot det totale museum. Henie Onstad Kunstsenter og tidsbasert kunst, 1961–2011 (Oslo: Henie Onstad Kunstsenter, 2011).

-

Seeds for a Random Garden (1972) is the title of a work by Joan Hills, included in the catalogue section of this essay. Henie Onstad presented an exhibition dedicated to the Boyle Family Archive, of which Joan Hills is a part: Boyle Family: Contemporary Archeology, curated by Lars Mørch Finborud and held April 20–September 2, 2018. The family’s artworks have been in the collection of the museum since the mid-1980s.