Hverdagen har blitt synlig

↑ George Maciunas, Same Card Flux Deck, 1983. ReFlux Editions (Originally 1966).

The Ken Friedman Fluxus Collection Henie Onstad Kunstsenter. Photo: Øystein Thorvaldsen.

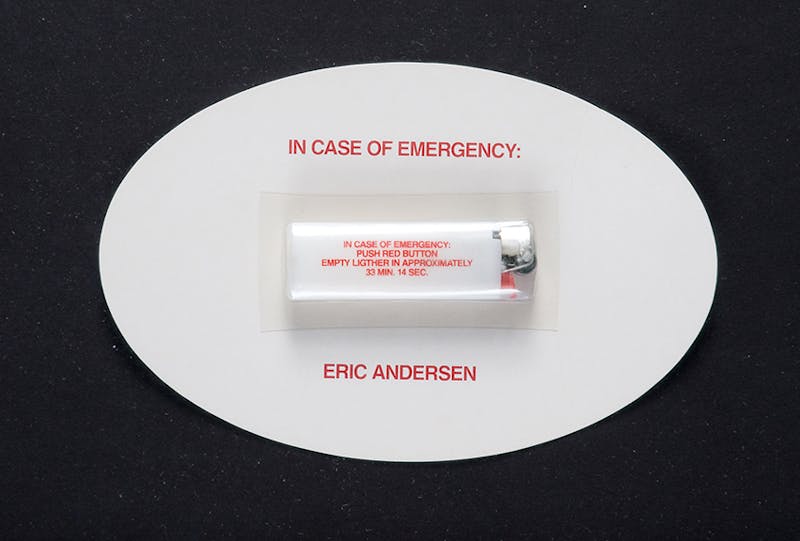

↑ Eric Andersen, In Case of Emergency, 1980.

The Ken Friedman Fluxus Collection Henie Onstad Kunstsenter. Photo: Øystein Thorvaldsen.

Hverdagen har blitt synlig

Since spring 2020 large parts of our community functions were put on hold. Everyday life as we know it has been turned up side down.

Some very few could experience the shutdown as something resembling a holiday while sharing images on social media of their very first sourdough bread, as Aftenposten (the main daily newspaper in Norway) wrote in their article «Believes in increased status for everyday life, home growing and local communities» on April 28th 2020. All while staying indoors without swiping the credit card at whichever restaurants, travel agencies or stores that used to be the lively hood of other people in the big machine that is our society. Home office was not an option for people in the latter group. That we are now turning toward an everyday life and becoming aware that such a thing exists, is productive. But what is this everyday life that we keep talking about and what potential does it have?

Everyday life is apparently a self explanatory phenomenon. It revolves around the «little things», routines and habits that we have created our lives around. But it is far from obvious what everyday life really is. Is it the entire social world? Specific chores and habits? A certain attitude or relation to one’s surroundings?

Everyday life is apparently a self explanatory phenomenon. It revolves around the «little things», routines and habits that we have created our lives around. But it is far from obvious what everyday life really is.

The Ken Friedman Fluxus Collection Henie Onstad Kunstsenter. Photo: Øystein Thorvaldsen.

The Ken Friedman Fluxus Collection Henie Onstad Kunstsenter. Photo: Øystein Thorvaldsen.

Historically, everyday life has been associated with the repetitive and by the grey and boring days but it has also been a source of collective engagement and revolution articulated by the Avant-garde movement of the 1900’s, among others. The end of the 1950’s and in the beginning of the 1960’s, when the Western world was rebuilding after World War II, is an especially productive period when it comes to understanding the potential of everyday life. In just a few years, new technology, city development and new houses changed the way of life for most people. We became the modern society of consumption.

Among those who gave a lot of attention to the new everyday life we find the international movement International Situationists. With the new consumer society, everyday life is no longer about living but about having, claimed the legendary theorist, filmmaker and cofounder of International Situationists, Guy Debord in the book «The Society of the Spectacle» (1967). Everyday life had been alienated and «colonized» to the degree that we no longer control it. It is a deeply rooted social change where any notion of the authentic has become impossible. The quality of life in the Society of the Spectacle is disgraceful Debord remarked, associated with a decline of knowledge and critical thinking.

«To study everyday life would be an absurd undertaking, unable to understand anything at all about one’s object, unless the study was conducted explicitly with the intention to transform everyday life», claimed Debord in 1961 and offered, along with his peers, a reservoir of practices and activistic strategies with the intent of changing the spectacle itself. One of the most known strategies was dérive which means «to drift» or wander around the city to experience how the different environments we pass inadvertently can change our mood and psychology. This is about letting go of a goal-directed wandering and instead open up to a playful and constructive journey. I will leave it here as good tip in these times.

Many claim that the critical analyzes Debord made of the modern society has become ever more relevant. Because in our time we continue to carry out an everyday life governed by forces greater than everyday life itself, whether they be financial, political or environmental. So why should we care about everyday life in the light of the corona crisis? How should we care about it?

A lot can be connected to what we identify as everyday life but everyday life is not a quality of these things or even the sum of them. Everyday life is rather the entwinement of the things that we do, day after day together, and that make them a part of the diversity of our lived experiences. Walking to work, eating dinner or hitting the gym are all objective phenomenons - but everyday life invokes something which hold these things together, their continuity and rhythm, or lack of it. This has to do with the individual or collective «art of living».

A significant idea in much of the literature on everyday life is that at the same time as everyday life is being controlled by forces greater than itself, it can also be a positive resource, a source of change and greater ownership of one’s life. The key is to give it attention, like a common experience, shaped over and over again by people’s doings and encounters.

Everyday life is about taking care of oneself but it involves the community. Everyday life is everyday life because it is not connected to something miraculous, magical or holy. Everyday life is a democratic resource and it is collective because it acknowledges that we all share a worldly and material attachment to the world. No one, from the most famous to the least visible, escapes everyday life. Everyday life is an experience we share and is only made visible through what we do in time as well as space, in society as well as by ourselves. The challenge of everyday life has to do with our possibility of appropriating it.

In the work to be done in order to reorient society after the global, financial and medical emergency we are now experiencing, the point is that everyday life can be brought up as a resource of a new way of thinking. It is about something bigger than a few of us being able to bake bread or grow your own produce at home. In everyday life lies the potential to renegotiate the power of the subjective in relation to a wider political one; to influence by taking back ownership of the strategies of everyday life or forms of practice, and (in time) put proximity before distance, slow before efficiency, intuition before that which we can measure and quality before quantity. «Everyday life» writes Debord «is the measure of all things». Paradoxically, the corona epidemic has also enlightened this by making everyday life so visible to us.

Caroline Ugelstad is the head curator at Henie Onstad Kunstsenter and has a PhD in everyday life in relation to the 1960’s artist movements International Situationists and Fluxus. The text has originally been printed as an essay in Dagsavisen.